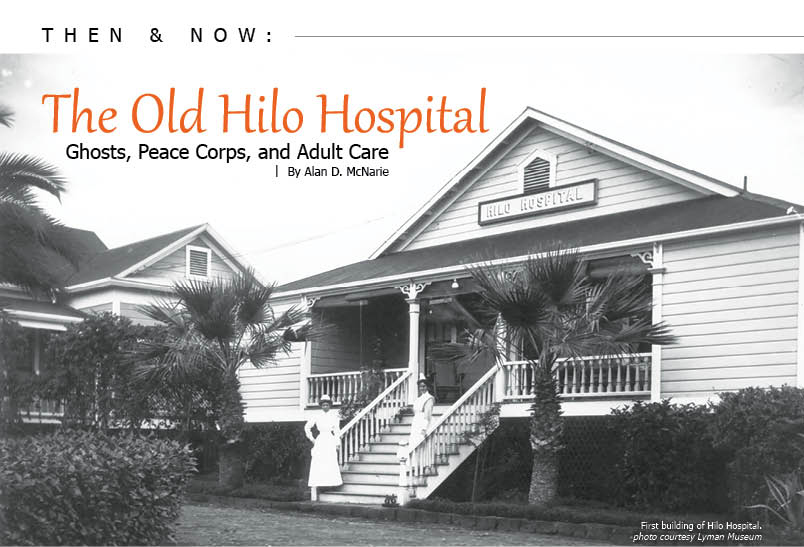

Then & Now: The Old Hilo Hospital

“Yes, there are ghosts,” says Lizby Logsdon. “Most people would agree. I haven’t heard anything recently, but it’s not uncommon for the elders to hear children outside playing when there are no children outside.”

“Yes, there are ghosts,” says Lizby Logsdon. “Most people would agree. I haven’t heard anything recently, but it’s not uncommon for the elders to hear children outside playing when there are no children outside.”

Lizby is the Community Outreach coordinator at Hawai‘i Island Adult Care, which has occupied the old Hilo Memorial Hospital building for the past four decades, providing East Hawai‘i’s elderly residents a safe place to go in the daytime and their relatives with some respite from constant caregiving.

However, a person doing a Google search of “Old Hilo Hospital”, will find far less about senior care than they will about ghosts. “Paranormal investigators” have posted various videos showing them prowling around the building and grounds at night with various electronic gizmos, searching for poltergeists. And Lizby has had at least one weird experience of her own.

“One evening, I had to go back into the Golden Heart Wing,” she recalls. “Just upon getting to that entrance, I kind of got the oojies. I found a line of crayons between the tables, heading into the shower room. I went back out to the main floor where my coworkers were, and my coworkers were all staring at me and asked, ‘What the heck happened? You look like you’ve seen a ghost.’ ”

The playful child-spirits are gentle souls, never reported to have harmed anyone, if they exist at all. The ghost hunters often tell a story about a fatal fire in the old hospital’s children’s ward. However, no date is ever given for the fire.

The late historian Kent Warshauer, who for years wrote a popular Hawaii Tribune Herald column called “The Riddle of the Relic,” once devoted two long, meticulous columns to the history of Hilo’s hospital system; after going through the county’s records of expenditures on the hospital from the moment the very first public hospital was constructed in the 1890s—and he never mentioned such a fire. Hawai‘i Island Adult Care’s social services coordinator, Tiffany Fisk, who’s talked to hundreds of Hilo seniors about their recollections of this building, has never found one who remembers a fire.

She’s learned the building is certainly haunted with memories, if not ghosts.

“While taking a Cultural Resource Management course from University of Hawai‘i Hilo (UH Hilo) Anthropology teacher Peter Mills, we had to complete a semester-long ‘adopt a site’ project,” she says.

“I adopted the Old Hilo Hospital site and spent the semester doing archival research and collecting oral histories. Many of the oral histories came from staff members, family members, and the kūpuna who participate in the program at my work. They shared stories of working as nurses at the Hospital; staff members shared that they were born in this hospital; a participant shared that her family was moved to this property following the 1946 Tsunami when her house was destroyed. I was amazed by the number of people in the Hilo community who had many personal stories to share about this property.”

After it closed as a hospital, the building continued to play various active roles in the community. It’s hosted several government agencies, including the prosecutor’s office and, most recently, the new UH Hilo College of Pharmacy, as well as the adult care center. For several years, it hosted a training program for Peace Corps volunteers on their way to various countries in Asia and the Pacific.

Embedded in that history is a record of a society that’s changed vastly over the years, both in its institutions and its attitudes. The old Hilo Memorial, in all its incarnations, played an active role in that change. It was “the first integrated care facility that I’m aware of” on the island, says Tiffany.

In the island’s early territorial days, many residents relied on separate plantation facilities for medical care. When the very first “public” hospital was built in the 1890s, British residents raised money to open a separate ”Queen Victoria Annex” to be reserved for “Anglo-Saxon” patients.

Hilo Memorial was constructed in the Italian Renaissance palace architectural style. According to Kent, once all the patients had been moved to Hilo Memorial, the previous hospital was dismantled and materials from it were used to create outbuildings for the new hospital—including maid-servants’ quarters, a manservant’s quarter, and a cook’s and head orderly’s cottage. A nurse’s dormitory was also built; as with the plantations, institutions such as hospitals in those days were expected to supply housing for their employees.

The hospital continued to expand in the 1930s and 40s with the additions of a maternity ward, solarium, isolation ward, and “Ward B,” according to Kent. He noted, “By 1955, Hilo Memorial Hospital was aging poorly [and] lacking money, the Board of Supervisors voted in July to convert a portion of the Puumaile Tuberculosis Hospital into a general hospital to replace the decrepit Hilo Memorial.” The tuberculosis hospital, located on the site of the current Hilo Medical Center, had been superannuated by modern antibiotics that effectively combatted tuberculosis, not by termites and rot.

The new hospital opened on March 18, 1961, and Hilo Memorial, “aging poorly” or not, was still too valuable to simply tear down. It entered its first post-hospital incarnation as “Rainbow Falls Home,” a care facility for the aged.

It soon had a new tenant. Eighteen days before Rainbow Falls Home opened, President John F. Kennedy had signed the bill that created the Peace Corps. Thousands of volunteers answered his call to “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” In the fall of 1962, the Corps selected Hilo as its training center for volunteers headed for Southeast Asia and the Pacific. The County of Hawai‘i agreed to let the Peace Corps training program use the old hospital building as its headquarters. UH Hilo, then called Hilo College, collaborated on the curriculum. Training sites were set up around the island—including a mock-Southeast Asian village in Waipi‘o Valley. The trainees generally stayed in the old nurses’ dormitory at the former hospital and went to classes in the main building. According to one volunteer’s account, the trainee’s dining hall was set up in the former morgue.

Not that the food was anything to complain about.

“The food was so good that we gained some weight before we went off to other countries and lost it again,” recalls Patricia (Pat) Richardson, who trained in Hilo in 1963.

They also had opportunities to work fat off. Some aspects of this early training program—especially its physical training, would have surprised later Peace Corps veterans. Volunteers learned canoeing in Hilo Bay, did calisthenics at Hilo High School’s gym, took swimming courses at the NAS Pool near the old Hilo Airport, backpacked in and out of Waipi‘o Valley, and even hiked to the top of Mauna Kea.

The political indoctrination might be a surprise, too. Again, it was a reflection of a different time: the U.S. was just beginning its involvement in Vietnam, and the government wanted its Peace Corps emissaries to know exactly what they were representing. So in addition to studying the culture of their host countries, says Pat. “We had American Studies, where they made sure we were well brainwashed with our country and our way of living,”

Hal Glatzer remembers American Studies, too. He arrived at the Hilo training center in 1967.

“We had to read The Ugly American and [Anthony] Burgess’s The Long Day Wanes,” he remembers. “We represented America. We were not allowed to criticize the war.”

Peace Corps Volunteers didn’t go to Vietnam from Hawai‘i. Instead, they trained here for other Southeast Asian nations, including Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines—and some countries that don’t exist anymore. The same colonial mentality that was fading in the new State of Hawai‘i was also disintegrating worldwide. Pat, for instance, was recruited to go to Saba, which was then part of the British colony of North Borneo. By the time she arrived at training, Saba had gained independence.

To all of that political uncertainty, physical exhaustion, and cross-cultural stress was added a vigorous weeding-out process. Several of Pat’s classmates washed out and never made it to their assigned posts. There was one consolation: “I’ve had three months in Hawai‘i, how can I lose?” she decided.

Hal also felt that consolation. Also recruited for Malysia, he’d grown up liberal and Jewish in Manhattan; the more he learned about his destination country, which was predominantly Muslim, the less comfortable he felt.

“I was not an ideal candidate, at least not for Malaysia,” he recalls.

Eventually, he “deselected” himself. Meanwhile, he’d fallen in love with Hawai‘i. He decided to stay, and has since had a successful life as a musician, actor, mystery writer, and general cultural force. Malaysia’s loss has been Hawai‘i’s gain.

Pat did go to Saba, where conditions weren’t nearly as strenuous as she’d expected; her bungalow there, she says, “was nicer than any quarters I’d had in college.” She liked it so well that she stayed an extra two years. She also had caught the spirit of Aloha. After returning to Michigan for a year, she found a teaching job in Hawai‘i, and has lived here ever since.

The program in Hilo trained an average of about 1,300 volunteers a year and continued until 1971. Eventually, the Peace Corps decided to move its training to the host countries, where volunteers could train intensively all day and then practice their language and cross-cultural skills by ordering dinner at a local restaurant at night. The American Studies and the calisthenics have long since been dropped. The current training still retains many lessons learned at the Old Hospital. Both Hal and Pat frequently use the word “wonderful,” when describing their stays at the old nurses’ quarters.

“I think the later plan [to train in the host country] is better, but I’m glad I had the luxury of training in Hawai‘i. It was a real privilege. It was real treat,” says Pat.

Among her memories is one grim moment: she was in training the day that President Kennedy was assassinated. When the volunteers heard the news, they began raising funds for a memorial inscribed with the words from his famous “Ask not…” speech, which was erected on the Old Hospital grounds. It’s since been moved to UH Hilo and serves as a monument to Kennedy, and to the volunteers themselves. (see photo on page 14)

Today, many residents born in Hilo Memorial are returning there daily, creating one last set of memories to embed in the old building. They meet old friends, take part in classes and activities, go on field trips, eat meals together, and exercise according to their abilities. Their families get respite from constant caregiving, and they get to sleep in their own homes at night.

“Some people [program participants] are really happy and proud to be here, because it saves their family’s lives,” says Lizby. “It gives people a sense of purpose.”

Even buildings grow old and die. The Nurses’ Quarters and several other outbuildings have been demolished, and one wing of the hospital itself has been condemned. Hawai‘i Island Adult Care will be moving to its own new building in three to five years. After that, the prospects for the Old Hospital are bleak. According to Tiffany, the building was once on the State Register of Historic Places, then at some point it was removed. It stands little chance of preservation unless it gets back on the Register.

When she was interviewing those hundreds of people about their memories of the place, she always asked if they thought it should be preserved. “All but two said yes,” she says.

Suggestions for future use include an art/cultural center, a Hawaiian Culture Center, and a botanical garden on the building’s 32-acre grounds. However, any restoration would require millions of dollars.

Memories, sometimes, don’t come cheap. If the hospital is demolished, where will the ghosts play? ❖

Contact Hawaii Island Adult Care, 808.961.3747

Contact writer Alan D. McNarie