Songbirds of Miloli‘i: Nā Kūpuna, Nā Keiki, and Diana Aki

Diana Puakini Aki had already acquired the nickname “The Songbird of Miloli‘i” when she received the Female Vocalist of the Year award for her debut album, Memories of You, in 1990. One of the songs on it is a haunting and melodic version of “Songbird.”

Diana Puakini Aki had already acquired the nickname “The Songbird of Miloli‘i” when she received the Female Vocalist of the Year award for her debut album, Memories of You, in 1990. One of the songs on it is a haunting and melodic version of “Songbird.”

The girl with the clear, sweet voice from the village at the end of the road had also attracted the attention of other famous musicians, including Eddie Kamae and Israel Kamakawiwo‘ole, who traveled to the remote Hawai‘i Island fishing village of Miloli‘i just to find out more about her and the old Hawai‘i songs that she sings. They were so touched by the village’s people and the passion with which they sang that they both asked permission to record songs they heard Diana sing there.

One of them is “Lā ‘Elima,” a poignant song telling the story of the 5th of February, a day in 1868 when the children of the village were swept away by a tsunami—and then a miracle occurred.

Aunty Diana, who is a wonderful singer and a consummate storyteller, tells the story and describes the unique style of singing that she learned from her auntys. “Their way of expressing the song was to prolong it, like wailing, or like a chant. There’s a song that talks about the day when a great wave came in. Everybody was having a celebration down by the park. Because it was a long way down to the village, when the families all got together they would stay for days. Somebody yelled, ‘Auwe! kai miki, kai miki [tsunami]!’ When people hear that, everybody runs inland, along the ala nui, the pathway. They got to safety then turned around, and they noticed the children weren’t there. They started to wail, ‘Auwe, eia nei, pepe [come here, baby].’ This one wave took the entire village, including the Protestant church.

“Then the miracle happened. When the water started leveling off, they started noticing splashes in the water. They all started running toward the sea. Sure enough, they started pulling the children up. Of all the area on that south side of Kona where the water came in, we were able to save all of our children. So they wrote the song ‘Lā Elima.’ It says on the 5th of February, tears fell along the pathway. Now I don’t have the long breath that you needed. Brother Israel fell in love with the song and recorded it. It’s more in the modern style. In the old style, you just wail like you feel.”

Diana, who was born and educated in Hilo, then moved to Miloli‘i at age 11, says she is not the one songbird of Miloli‘i, that there were many, especially her auntys who taught her how to sing local style. “I was the one that was inspired by them. You don’t sing any kine; you sing what you feel.”

Because her father’s family was from Miloli‘i, the family moved back there when he fell ill. Her parents wanted her to continue her schooling, so she lived part of the time with relatives in Hilo and traveled back and forth.

“There was hardly any access to get out of that place. The road wasn’t oiled either, it was just a donkey trail, covered by trees. It was like going into a cave going down there. When it came time to go to school, I came back to Hilo. I was attending St. Joseph School, so it was a big deal. There were hardly any Hawaiians in that school.”

It was in Miloli‘i, she says, that “I found my Hawaiianness.” Hawaiian was still spoken there as the primary language, so she just listened.

“It was kind of lonely at first, I felt alone. The cousins and children my age never bothered about me. I was always with the elders, the older ones. That’s where I learned. Two of my aunts, the Grace sisters—Kalua and Rosaline—were the ones that really kept the music going, always singing the old songs. I started to learn [the language], but the songs spoke to me. Hawaiians are very observant and I would observe more than I would speak. Humility counted. You just humble yourself and behave.”

The village was then and still is known as a traditional fishing village. “I had to learn how to adjust myself to that lifestyle. It was different than the city. We all had to go out on the fishing boats. The kūpuna told stories about how in the old days they traded their fish. The coconut and lauhala hats were made, and all of the salted fish placed in a barrel, and the boats would come and take it away. When they came back, they would bring the crackers and the coffee. The people would also make exchanges with other families that lived up along the highway. We lived with nature. When it was hot, we’d sit in the shade and make fishing lines and hooks and things like that.”

Diana married a Hilo boy, Fidelis Aki. “He came to Miloli‘i for me.” He, too, became a fisherman. Together, they had seven sons and adopted two girls.

Diana’s life has been more than music and fishing. She has also been an early childhood educator, working for Kamehameha Schools. The first opportunity she had was to help the children of Miloli‘i, including her own.

“They had to get up so early and go all the way up to the top to catch the bus and drive to school in Ho‘okena. The children were having a hard time functioning; they were falling asleep, so they started a little boarding school nearby, and I was one of the dorm attendants there. I lived up there on weekdays and came home on weekends.”

She loved working with the children. In 1978, Kamehameha Schools started an extension program in Hōnaunau, adjacent to the Place of Refuge (Pu‘uhonua o Hōnaunau), Diana said.

“It was called Hale Ho‘oponopono because it was a place to find yourself.

They took in students coming from Konawaena School, where Hawaiian students were dropping out and getting into trouble because they couldn’t adjust. Their lifestyle was more like survival rather than getting educated for the future. So, this group of gentlemen from Honolulu said we need a program to start bringing the Hawaiian children together in schools.”

Diana caught their attention with the boarding school at Ho‘okena, and they hired her.

“I was hired as a resource person, because I knew the lifestyle. I knew how the Hawaiian thinks, and I applied that to handling situations with the children. I didn’t get hired on the kine degrees,” she said, laughing. “It was my first experience with wanting to be educated. I got the opportunity to go back and get my GED. I would finish in Hōnaunau, then go up to school at Kealakekua, then go home weekends.”

She spent 14 years with Hale Ho‘oponopono, until it ended and she transferred to Kamehameha Schools’ early childhood development program, where she visited families having a first birthing experience—mostly teenagers, she says.

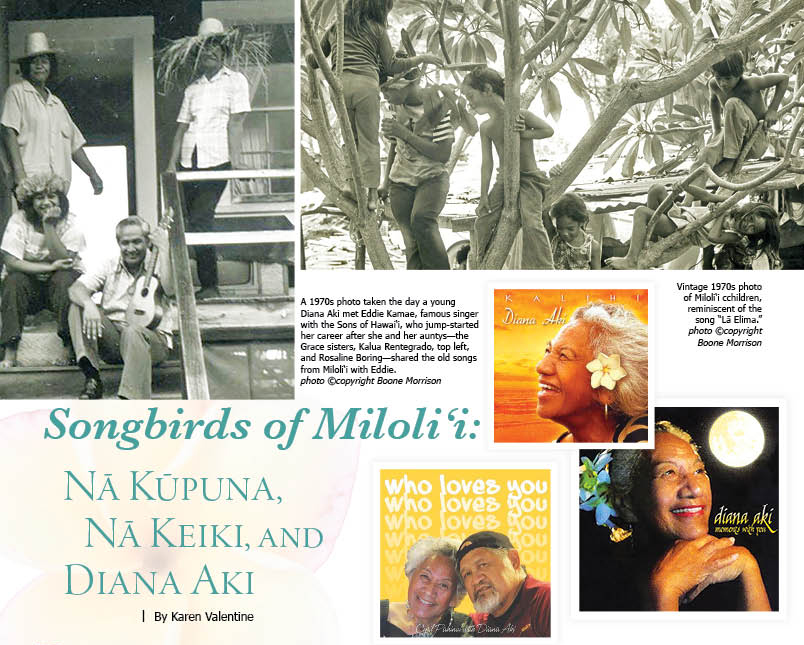

In the village, people often hired her to sing at their lū‘au and other occasions. Then an event happened that would expose her to the wider world of Hawaiian music. Photographer and architect Boone Morrison from Volcano had received a National Endowment for the Arts Photographer’s Fellowship in 1972 to document the rural village of Miloli‘i. During the two years he stayed there, he got to know and hear Diana Aki.

“He would come down and hear me sing with my other songbirds at parties. He saw what I was doing with the children and sharing the culture. He invited me one day to bring the children and give a presentation in South Kona about the songs we sing.

“The next morning, Boone came and said, ‘Guess who I brought? Eddie Kamae! I said, ‘Eddie Kamae! What did you bring him here for?’ He said he was there last night and he heard you. So I fixed him pancakes, and he was really kind. He says ‘I came because I was interested in the songs that you sing.’ I said, ‘They are not my songs; they belong to the auntys. They are the keepers of those songs.’ I said, ‘If you are interested, I’ll take you over there and you ask them.’ ”

After introducing the famous singer from the group Sons of Hawai‘i, Diana walked outside and waited patiently. “All of a sudden, Boone comes out and says, ‘You gotta go in there.’ Why? What’s happening? Aunty looked at me and at him and said, ‘If she sing the songs, you can have them.’ And that’s how I became famous, how I got started.”

So Aunty Diana went to Honolulu to sing her songs with Sons of Hawai‘i in 1978, and then joined them on tour to the other islands. While on Kaua‘i, she was inspired to write the song, “Mana‘o Pili” about how she loved that island.

Because of family obligations, Diana wasn’t able to continue on tour, and she returned to her home island, where Boone helped her to get a contract to sing at the Volcano House Hotel. She sang with Morrisonʻs group, the Volcano Hawaiian Band, and during those years, she met several other musicians, including Elias Kuamo‘o from Puna. He became a regular guitar player with her and one day convinced her to make a recording in a coffee shack in Kona.

They selected several of her songs in Hawaiian, four original compositions and some favorite contemporary songs, including “Songbird.” It became her first album, Moments With You. It was entered in Nā Hōkū Hanohano awards competition, where she was honored with Best Original Song (Haku Mele) for “Mana‘o Pili” and the 1990 Female Vocalist of the Year.

“When I made my debut,” Aunty Diana says, “I brought it home, and the first people there who heard it were my two aunts and they loved it. They asked why I didn’t sing everything in Hawaiian—that it should be all Hawaiian. I said, ‘But hey tutu, I won!’ ”

Two more Diana Aki albums have been released. One is Precious Hawai‘i, recorded by her, and published without her permission. Her latest is Kalihi in 2009.

In 1998, Diana and her husband returned to Hilo, where their lives would be more convenient. (“And Hilo has hot water!”) All the children were grown and Fidelis needed medical care. He passed away in 2003. Diana continued working in early childhood education for Kamehameha Schools in Hilo before retiring.

The Songbird of Miloli‘i still keeps up a regular schedule of performance dates and rarely gives up an opportunity to share her songs and her mana‘o. She has also appeared on numerous albums with other artists, such as Cyril Pahinui and George Kahumoku, as well as on compilation albums of Hawaiian music. Other artists have recorded her original compositions, too, which include

“Mana‘o Pili,” “Moments With You,” “Manu Mele,” and “Aloha Hale O Ho‘oponopono,” the last one written by the staff and children at the school.

“They call me the Songbird of Miloli‘i, but I say there were more songbirds before me,” she humbly reminds us. “What I gathered from all those experiences is not the way you sing, it’s the way you feel. For me, that’s what makes me want to sing.” ❖

Contact Diana Aki: 808.238.2383

Contact writer Karen Valentine