Alternative Education for Hawai‘i Island Keiki

Chloe Smith would be homeschooled had it not been for West Hawaii Explorations Academy (WHEA). She and her peers interested in marine biology or aquaponics find refuge in their educational choice at the North Kona public charter school, a stone’s throw from the Natural Energy Laboratory of Hawaii.

Chloe Smith would be homeschooled had it not been for West Hawaii Explorations Academy (WHEA). She and her peers interested in marine biology or aquaponics find refuge in their educational choice at the North Kona public charter school, a stone’s throw from the Natural Energy Laboratory of Hawaii.

With 15 charter schools here on this island, some more than others have parents and children vying for a seat, either for the language and cultural aspect of the school, or for the fact that the school is project and place based. In upcoming issues, Ke Ola Magazine will explore those reasons and highlight the various schools offered here on this island.

Charter schools, as defined by the Hawaii Public Charter Schools Network, are public schools operated and managed by independent governing boards. They are innovative, outcome-based public schools operating under a performance contract with the State Public Charter School Commission. Although charter schools are funded on a “per pupil” basis separately from Department of Education-operated schools, charter schools are open-enrollment public schools that serve all students and do not charge tuition.

“It all depends on the person, because we are all self reliant here,” Chloe says of WHEA in particular. “My main things are school and surfing; I like being able to plan how I want to do it,” she says of school.

Chloe went to Fiji for a seahorse farm project in November. Her travel tied in with her school projects, so she arranged to receive school credit for the portion of the trip that was devoted to reef restoration and ocean conservation education. Trips like that don’t happen in a traditional DOE setting.

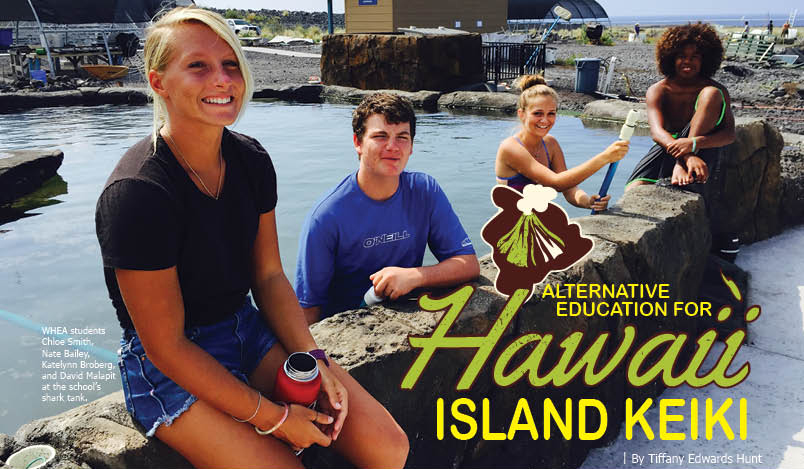

At WHEA, Chloe and fellow students are studying how long various organisms live in WHEA’s ecosystem, namely saltwater ponds situated in the center of the school. Inside a smaller pond are a variety of fish—sea cucumber and an octopus—and inside a larger pond is a black tip reef shark the students have named “Nala.” During Ke Ola’s recent visit, students cleaned the larger pond and gathered around the smaller pond feeding crabs to the octopus, counting and recording the number of crabs.

“It’s about what you’re interested in,” says Katelynn Broberg, a second year student of the school, as she cleaned the larger pond.

“For us, a lot of people want to go here, but can’t get in,” adds Chloe, who dropped crabs into the smaller pond for the octopus. The school has a lottery system to fill slots as there is limited space.

“It’s an alternative school, kind of like home school, but public high school for people who are self directed, and also for those who don’t want the traditional school,” says second year student Nate Bailey. He helped to clean the larger pond with Katelynn.

To think, WHEA started out with “nothing but gravel, people, and sky,” as a caption in one of the school’s photographs reads. WHEA morphed into a public charter school after starting out as a program within Konaweana High School, according to WHEA Secondary English Teacher Curtis Muraoka.

When Kealakehe High School was built, the funding for WHEA shifted from Konawaena to Kealakehe. Kealakehe High School principal Wilfred Murakami vowed to adopt WHEA but wanted to change the program, Curtis recalls. This was right around the time the Charter School law passed in 1999. Then WHEA Director Bill Woerner opted to try “this new thing” called the charter school and became one of the four charter schools in the state to start up with the new century.

WHEA started out with 75 students, then immediately expanded to 120. What kept the school afloat, Curtis recalls, is a National Science Foundation grant to do educational research.

WHEA is not a Title 1 school for underprivileged kids, so it has been, as Curtis describes, “a canary in a coal mine.”

“We were trying to not be the first school to close, operating with the least amount of capital,” further explaining his particular path to get politically involved in the charter school movement. Curtis has served as a statewide charter school commissioner (2013–2014) and as vice president of the Hawaii Public Charter School Network.

He sees three different kinds of students at WHEA: those who know what the school offers and want it; those who are interested and will give it a try; and those who consider it their last stop before dropping out.

“It goes back to school choice, Curtis says.

WHEA has prospered as well as a charter school can with its current funding structure.

A year ago, the school moved mauka of its original site that was too close to the water and in the Kona International Airport’s expansion area. “Through frugal operation,” Curtis says the school saved $1 million for its new campus. Then, Kona legislator Denny Coffman championed legislation Curtis says got WHEA a grant-in-aid award of $1.5 million in 2011. The school also received a $5.5 million USDA Rural Development loan.

“The school literally was built from scratch,” Curtis says. “The kids put up tents and then a portable, and then the Carpenter’s Union donated a workshop pavilion.”

Now WHEA boasts light emitting diode (LED) energy efficient rooms designed by Ferroro Choi, known for his sustainable design of the Amundsen-Scott scientific research station at the South Pole. WHEA is currently maxed out at 282 students.

While WHEA started out as a school within a school, other schools emerged with the passage of the Charter School law. Because they started up in the year 2000, many of the schools opted to name themselves “new century charter schools.” This was the case with Kua o ka Lā in Puna.

Even though Kua o ka Lā New Century Public Charter School got its charter in 2000, it took a couple of years to get organized. For the 2002–2003 school year, Kua o ka Lā had 26 students in grades six through eight. “We had no facilities. We had 600 acres, but no facilities,” Susie Osborne recalls. In addition to land adjacent to Ahalanui Park, or “Hot Ponds,” for the middle school, Kua o ka Lā partnered with Opihikao Congregational Church, namely John and Violet Makuakane, to form a kindergarten class.

“We added a grade every year until we reached 12th grade,” Susie says. Recently, Kua o ka Lā added a campus at Miloli‘i and started utilizing the Boys and Girls Club in Hilo as a place for students to connect with teachers in what Susie describes as a “blended online program.”

Hurricane Iselle and the lava inundation scare of 2014 heavily impacted Kua o ka Lā. The main campus on the Red Road (Kalapana-Kapoho Rd.) adjacent to Hot Ponds was directly hit by Iselle and incurred a lot of damage. Kua o ka Lā got a double whammy when the Federal Emergency Management Agency didn’t cover most of the school’s claims, and a lot of the community left the area for fear of being isolated by lava.

In the last year, Kua o ka Lā saw a drastic drop in enrollment and had to cut its staff in half. Susie considers 2015 to be a stabilizing year. Currently Kua o ka Lā offers a standard elementary school with one grade per level, except for 4th and 5th grades, which are a combination class. Middle school and high school are smaller, more place and project based, or online. The elementary school offers a “wildly successful” culinary program, while the middle school students and high schools students are engaged in mechanics, wood-working, agriculture, aquaponics, growing native plants, oral history with kūpuna, and even data collection and educational awareness of

‘rat lungworm’ disease.

Kay Howe, a graduate student in tropical conservation, biology, and environmental science at the University of Hawai‘i, is working with charter school students to study ‘rat lungworm’ disease, or angiostrongylus. The disease is a parasite carried by rats and transferred to humans via flatworms or slugs. Experts believe contaminated produce is the vehicle through which humans are ultimately infected.

Kanu o ka ‘Āina, Laupāhoehoe, Volcano School of Arts and Science, Nā Wai Ola, and Kua o ka Lā public charter schools have all partnered with University of Hawai‘i Hilo to help prepare an integrated pest management plan to control invasive slugs and snails. This pest management plan is geared toward preventing angiostrongylus, Kay says.

The goal of the charter school involvement is to ensure education is embedded in all school garden projects, the graduate student says.

“Why did I pick charter schools? Because they really embrace this type of thing. They are less regimented in their delivery. They really embrace placed-based, project-based learning. My goal is to have this be an integrated curriculum. It’s a way to get kids involved as educators for their community, and we really need that. To me, one of the most efficient ways to reach hard-to-reach rural populations.”

Meanwhile, back at Kua o ka Lā, the school is among the public charter schools statewide that defy the lack of facilities funding from DOE. Kua o ka Lā operates with per-pupil funding and any grants received through its nonprofit arm.

Over the years, Kua o ka Lā has been able to build classrooms, yet is still struggling to save up for a certified community kitchen and toilet facilities. Students and staff use portable restrooms, and lunch is prepared and shipped from the Hawai‘i County Economic Opportunity Council’s certified kitchen in Hilo.

Susie says the school has the septic system for the restrooms; all that is needed is the capital for the building. She envisions a certified kitchen that could serve the greater community.

“If I can have a certified kitchen here, not only will it serve farmers and those at farmers markets in need of the community kitchen, it will be an incubator kitchen for the community,” Susie says. Kua o ka Lā is talking with Hawai‘i Community College about partnering for extension education programs in the kitchen to come.

Currently, students receive college credits working with the Hawaii Youth Business Center doing digital media arts. Those students are working with PBS Hawaii’s Hiki Nō program. A Kua o ka Lā student in Miloli‘i did a story on Mauna Kea telescopes and won an award for his script.

“It’s more hands-on activities. It’s a smaller school, smaller more nurturing environment, smaller class sizes, more attention, because everybody here knows everybody, and of course the cultural component, those are the top three,” Susie says.

“Every school is unique,” says Ke Kula ‘O Nāwahīokalani‘ōpu‘u School Administrative Services Assistant Kamalei Hayes. “I think we focus more on language and culture, but more of the language part.”

Ke Ola Magazine will explore Ke Kula ‘O Nāwahīokalani‘ōpu‘u Iki Lab Public Charter School in Kea‘au, along with other language and culture based schools island-wide in the next installment of this series on alternate education. ❖

Contact West Hawaii Explorations Academy, 808.327.4751

Contact Kua o ka Lā, 808.965.5098

Contact writer and photographer Tiffany Edwards Hunt

Directory of Hawai‘i Island Charter Schools

East Hawai‘i Island

Connections Public Charter School, 808.961.3664

Hawaii Academy of Arts and Science Public Charter School, 808.965.3730

Ka ‘Umeke Ka‘eo Public Charter School, 808.933.3482

Ke Ana La‘ahana Public Charter School, 808.961.6228

Ke Kula ‘O Nāwahīokalani‘ōpu‘u Iki Lab Public Charter School, 808.982.4260

Kua O Ka Lā New Century Public Charter School, 808.965.5098

Laupāhoehoe Community Public Charter School, 808.962.2200

Nā Wai Ola Public Charter School, 808.968.2318

Volcano School of Arts and Sciences Public Charter School, 808.985.9800

West Hawai‘i Island

Innovations Public Charter School, 808.327.6205

Kanu O Ka ‘Āina New Century Public Charter School, 808.890.8144

Kona Pacific Public Charter School, 808.322.4900

Ka‘u Learning Academy, 808.498.0761

Waimea Middle Public Conversion Charter School, 808.887.6090

West Hawaii Explorations Academy, 808.327.4751