Mele Murals: University of Hawai‘i Hilo, part 1

Cultural preservation is not merely curating artifacts. It is a dynamic process, which imbues new generations with the ethos of their progenitors, while allowing them to evolve to meet the challenges of a changing world.

Cultural preservation is not merely curating artifacts. It is a dynamic process, which imbues new generations with the ethos of their progenitors, while allowing them to evolve to meet the challenges of a changing world.

The arts are an important part of this process, recording history, myth, and legend, preserving the past, informing the present, and extrapolating the future. Through the Mele Murals public art project, people can see this process in action.

Firmly rooted in Hawaiian cultural traditions, the movement uses mele (songs), oli (chants), and mo‘olelo (stories with an intent to inform and educate) as a vehicle for collaborative murals in public places.

Each mural is created by a Hālau Pāheona (visual arts school). Area kūpuna (elders) and kumu (educators) guide the participating youth and artists, as well as the larger community, to explore the mana‘o pili pono (literal meaning) and kaona (poetic hidden meaning) of the mele and mo‘olelo. This exploration includes relating the themes of this oral tradition to past and present community issues. The artists then help the youth to create a mural expressing this collaborative mana‘o through their own visual metaphors.

The hālau teaches the oral traditions and visual arts, as well as traditional Hawaiian core values.

The process, designed by the Estria Foundation, is a youth development, arts education, cultural preservation, and community-building project. The completed murals give nā ‘ōpio (youth), makua (parents), and kūpuna a way to share across generations, between cultures, and with malihini (visitors) to the community.

Starting in late 2013, local artists, youth, and other people in communities across Nā Moku ‘Ewalu—Hawai‘i’s eight islands—have been participating in creating the Mele Murals. So far, on Moku Hawai‘i, there are murals at the Kahilu Theater in Waimea (Jul–Aug 2015 Ke Ola), at the Keauhou Shopping Center in Kona (Sep–Oct 2015 Ke Ola, Nov–Dec 2015 Ke Ola), the University of Hawai‘i Hilo (UH Hilo) dorms, and the Sheraton Kailua-Kona.

The Murals of UH Hilo

One of the midwives of the project, Mahea Akau, reflects, “Why did I get involved in this project? It is pretty simple…kuleana.”

Mahea continues, “Although I was not a part of the Mele Murals conceptualization process, I have been with The Estria Foundation since 2013 and have managed the project since then. I have been given some amazing opportunities in this life, but this, by far, has been the most rewarding.

“About three years ago, through a mutual friend, Estria reached out to me for another project he was working on called Water Writes. As we brainstormed ideas about Water Writes, he shared with me his mana‘o on Mele Murals. At the first mention of youth empowerment and cultural preservation, I knew it was something I needed to be a part of. And as Estria and I talked more and more about the idea of Mele Murals and infusing the popularity of street art into the project, there was something kū‘ē [activist] and edgy about it that I wanted to see come to life.

“Since then, I count my blessings every day to have the opportunity to be a part of something so progressive for our lāhui (nation, race of people)—especially our ‘ōpio (youth).”

Mahea recognizes the vast number of people it takes to create such a comprehensive program. “We have been very fortunate to have the support of so many across Hawai‘i. Mele Murals is a catalyst for change for our people and our communities; it excites me that we’re just getting started.”

Kamalani Johnson began his involvement with the program as a haumana in fall of 2014. He says of his first experience, “I was involved in a Mele Mural project as a student, as I was a senior in college” at UH Hilo. “My involvement was driven through my desire to impact the population of students in the UH Hilo community…I served as a primary cultural component for the creative piece of the mural.”

He found the experience so rewarding that this past summer he participated as a professional staff member—Activities Coordinator for the Kupa ‘Āina Summer Bridge Program of UH Hilo. He says, “The second time, my involvement was driven as a staff member of the program coordinating the mural, and as I was involved in the creative piece of the first mural, I had previous experience in giving direction to the creativity of the mural and in achieving the goal in the time allotted.”

Hilo being Hilo, water is a recurring theme in both murals. Ua (water from the sky), wai (fresh water), and kai (salt water) are depicted with realism and symbolism.

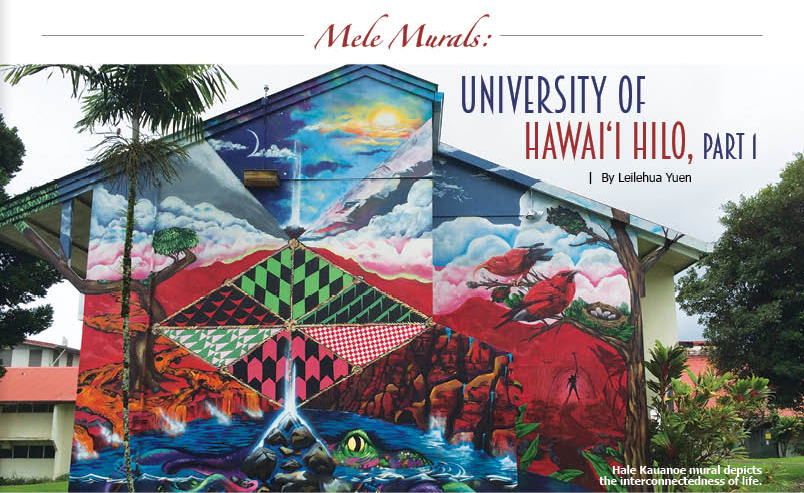

The first mural, which Kamalani worked on as a student, covers a two-story end wall on Hale Kauanoe in the freshman housing section. In planning the mural, students made use of the architecture. A doorway becomes a cave with the mo‘o (lizard/dragon) Kuna peering out, the grey rocks he clutches fading into the grey concrete. A closer look into the cave reveals the waterfall that guards Hina. The stairwell window reflects the clouds in such a way that they appear to continue unbroken across the surface. Knee braces become tree branches. Even the landscaping is incorporated, with the tī plant growing beside the dorm echoed in the painted leaves growing beside the pond.

The imagery is filled with kaona, the deep poetic meaning that gives mana, spiritual strength, to works of art.

The university and dorm stand where Mokaulele Forest, renowned for its scarlet ‘ōhi‘a-lehua, once grew. The forest was filled with the equally bright ‘apapane and ‘i‘iwi birds. These, too, are depicted on the wall.

On the edge opposite the ‘ōhi‘a-lehua stands a koa tree. Kamehameha Pai‘ea harvested the koa of Hilo—both wood and warriors—to build his peleleu fleet of conquest. Both koa and ‘ōhi‘a-lehua represent strength: Koa, the strong warrior, masculine and ready to fight; Lehua, the female warrior, fighting at need and regenerating after destruction.

From Mauna Loa, lava flows past the koa tree into the sea. The māhu (steam) of the lava meeting the sea is mirrored by the ‘ehu (spray) of Mauna Kea’s streams flowing into the ocean.

The moon, a symbol of Hina, a prominent goddess in Hilo traditions who appears in many aspects or as many sisters, is depicted in its Hilo phase—the first slim crescent visible after the new moon, and namesake of the Hilo district of this island.

To the right of the moon, Hānaiakamalama (Southern Cross) stands upright, denoting winter, the time of Lono and rain. At the division of night and day, a column of light flows between earth and sky. Below, the column returns as water flowing into the sea. The sun sets over the shoulder of Mauna Kea. In Hawaiian tradition, the setting of the sun, not the rising, signals the start of a new day.

A matrix of cordage contains more symbolism of land, sea, and sky, drawing all together in unity. Each section defined by the cordage holds symbolic themes of water and ancestry. Faces of kūpuna—ancestors—gaze solemnly from rocks, water, and clouds.

Triangle motifs repeat in the rocks, water, cordage, Mauna Loa, and Mauna Kea. Kamalani says these triangles represent the makawalu concept and the role that it plays in place based learning. It represents the dynamic Hawaiian world view of the physical, intellectual, and spiritual foundations of the cycles of life.

Kanaloa, embodiment of the ocean, one of the four major deities, is revealed in his he‘e kinolau, octopus body form. An ‘o‘opu, the fish that sought knowledge, rests on the rocks in the stream. In the distance stands Kāwili, the bird catcher of Puna.

It is Kamalani’s hope that freshmen who stay at these dorms will develop a strong sense of place and connection to Hilo through the mural, absorbing its lessons by seeing it as part of their landscape each day. He acknowledges the changes that have happened in Hilo, and sees telling the mo‘olelo, the stories, of this place through pictures as a viable part of preserving the heritage of this wahi pana—celebrated place. As a student, he came to believe so strongly in the mission of the Mele Murals, that as a teacher he returned to the program for a second, even more ambitious, mural project at Hale ‘Ikena.

Core Values of Mele Murals

- Ahonui—Patience, to be expressed with perseverance

- Aloha—Love of self expands to love of family, love of community, love of the whole world. If all our work is grounded in aloha, we come in peace, and everything will be all right. The fundamental Hawaiian Values that make up the meaning of Aloha in all that we do, are:

- Akahai—Kindness, to be expressed with tenderness

- Ha‘aha‘a—Humility, to be expressed with modesty

- Ha‘aha‘a (Pride and Humility)—We are humble, and we can take pride in our work at the same time. We finish what we start.

- Ho‘a‘ano (To take great risk)—Don’t be afraid to take chances with your art and your career. Probably every hero you have took chances and came up with something new. If you don’t explore and fail, you won’t come up with anything new.

- Ho‘oha‘oha‘o (Wonderment)—Explore the unexplored, be amazed at our world around us, and have fun!

- Ho‘ohui (Alliance, Connection)—Hawaiians believe we never walk alone. We are connected to the land, our ancestors, and to so many around us. Think of everyone first.

- Ho‘oikaika (To work hard)—Our work speaks for us, just like our artwork. When we half step it shows.

- Ho‘omaika‘i (Grateful)—We are grateful for all our blessings, and we always thank those who have helped us.

- ‘Ike ho‘omaopopo (Perceptive, Open Mind)—Lessons come when you least expect them. See opportunity everywhere.

- ‘Ike loa (Positivity)—We encourage and push each other farther with a great attitude.

- Kako‘o (To Support/Participate)—We are here to learn. Participating is one of the best ways to gain.

- Kōkua (To Help/Assist)—We actively offer help to those in need around us.

- Kuka‘i (Converse/Communicate)—We need communication to move forward as a team.

- Kuleana (Responsibility/Commitment)—We keep our commitments, even when the going gets rough.

- Kupa‘a (Allegiance/Team Work)—We work together to grow higher, faster. Think of the team before our own ego. Loyalty is not known until it’s shown.

- Kupono (Honesty and Transparency)—Being honest builds trust and loyalty.

- Lōkahi (Unity)—to be expressed with harmony

- Mahalo (Respect)—We respect each other, the land, ancestors, our differing viewpoints, cultures, and ourselves. Don’t litter. Showing up on time respects other people’s time.

- Maika‘i Loa (Excellence)—We strive to do our best in every aspect of our work. We set high standards for ourselves because that is the way to achieve more.

- Mālama ‘Āina (ame Malama i ka wai) (Caring for the ‘āina and the wai)—The land is a living being and we are its guardians. Take care of the earth, and it will take care of us and future generations.

- Mana‘o (Intention)—We state our intentions so that everyone knows where we are headed.

- Na‘auao (Learning)—Always seek learning. If nothing else, we hope you walk away with the lifelong hunger for learning and the tools to attain knowledge.

- ‘Olu‘olu (Agreeable)—to be expressed with pleasantness

- Pono (Proper, Righteous)—We do our best to be just and fair. We believe everyone should be treated fairly, and with dignity.

- Waiho (To table as in option to pass)—Once in a while we do not wish to contribute and that must be respected.

There are many steps taken on the path to a completed Mele Mural:

- Arts-interested youth, potential advisors, and organizations are identified and encouraged to participate.

- Teams of community leaders, artists, students, and musicians are assembled.

- Youth form a Hālau Pāheona (mural club) at their school or community center, and begin organizing their mural.

- Haumāna (students) participate in online art assignments on edmodo.com.

- Students with support from the Estria Foundation team secure a permissioned wall and gather community support.

- Cultural practitioners ground and ask the land and ancestors what should be painted.

- Instructors from Papakū no Kāmeha‘ikana teach the youth how to write and say an oli (chant) about the subject matter.

- An advisory group of Hawaiian music experts, and cultural practitioners help to pair lyrics to the subject matter.

- Workshops are held on the song’s history, on how the mele relates to the place, and on the mural process.

- Haumāna ground and receive ideas for the mural.

- A sketch of the mural is developed by team of artists based on the workshop dialogue and incorporating some of the lyrics.

- The team grounds and asks if the sketch is pono (just, proper) before painting.

- The mural location and team are blessed by a kahu.

- The mural is painted by artists together with youth.

- The mural is unveiled at a community celebration.

- Youth muralists who have completed murals become Mele Murals docents and stewards, and mentors to future youth muralists.

- The entire process is documented through photography, film, social media, and published materials.

- Surveys are taken and reviewed to gauge program’s success. Changes are incorporated to improve effectiveness.

- The completed Mele Murals series provides opportunities for ongoing education, cultural tourism, and community development. ❖

Contact The Estria Foundation and Mele Murals

Contact writer and photographer Leilehua Yuen